French-Canadian voyageurs had one signature piece of clothing — their colorful wide woven sash.

Colin Pendziwol at Fort William Historical Park. (Photo by Jenni Grandfield)

Voyageurs exuded joy and verve. But, working on the lowest rung of workers in the fur trade hierarchy, they had few resources to express that lively style. Their shirts and trousers — made of homespun linen or linsey-woolsey — were worn hard, 24/7 in and out of the water, for 6 weeks or more. But men wanted to look their best, even with ragged, stained and patched clothes. A sash spiced up their tatty wardrobe.

So traditionally they stopped to freshen up at Hat Point — just out of Grand Portage. At the rendezvous, they’d notice the bourgeois in fancy city clothes. If they had a few coins to spend, they might trade for clothing.

Or, if they were headed for an interior post, canoemen might wait to trade with the Ojibwe for buckskins.

But whatever clothing they wore, a sash added sparkle and dash.

Fashion meets function: The OG utility belt!

Fingerwoven sashes. (Image by Marc-André Complaisance, Chaire du Canada Patrimonie ethnologique, Université Laval Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America)

Besides being striking — wrapped TWICE around a voyageur’s waist — it had multiple uses:

- holding a shirt down or trousers up (Belts hadn’t been invented yet.)

- a place to tuck a pipe, knife, fire steel or personal items (Pockets hadn’t been invented yet.)

- a cushion of support for 90-pound packs over a portage

- a temporary tumpline (or portage collar) to carry heavy items (Hernias were common among canoemen.)

- a tourniquet, sling or splint for an injured limb

- a rope

- a sewing kit (Individual strands could be cut from the fringe for a single thread.)

- it kept in warmth (In winter, a tightly-wrapped sash around a capote, the woolen blanket coat, trapped one’s body heat. (In Book 2: Treacherous Waters, André proudly wears a capote in his hamlet — his proof of being wintering.)

All red? Non! All the same? Non, non!

Native Americans, astute weavers of plant and animal fibers, created their own designs, incorporating beads into some of their patterns. The colorful voyageur sashes drew their attention.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

It led to a cottage industry for women in French-Canada — the most unique sash patterns were created in Fort Assumption, Charlevoix and Acadia. Designs included lengthwise stripes, chevrons, arrows and lightning bolts — each with its own story. At one time, a person’s community could be determined by the color and pattern of their sash.

BTW: They weren’t always red! Colors depended on what dyes the weaver had access to. Patterns were handed down from mothers to daughters, both Indigenous and French-Canadian, who finger-wove sashes for husbands, fathers and brothers. The finger-weaving technique is very different from using a loom. Making a plain sash might take 80 hours while a fine sash could take several HUNDRED hours!

Ray Meares featured Carol James, a sash-weaver in his documentary “The Company that Built a Country” (https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3601726/). It has fascinating info on the Hudson’s Bay Company and on canoe and voyageur crafts. Watch at about 24:30 when Carol demonstrates finger-weaving sashes that were 12 feet long and 280 threads wide, and describes how — and why — weavers changed the direction of the chevrons.

Identity and honor for the Métis

Louis Riel’s sash. (Image from the Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture)

Having participated in the fur trade, the Métis people adopted the sash as a symbol of their identity. The Order of the Sash is the highest honor that they can bestow.

Each color has significance: Red represents the historical red sash of voyageurs; blue and white for the Métis flag; green for fertility and growth; yellow for prosperity.

Black represents the dark period after 1870 when the Métis were suppressed and dispossessed of their lands by Canada. Resistance leader Louis Riel had been sheltered before surrendering in 1885; he gave his sash to the woman who’d protected him. That sash was passed to family members until it was acquired in 2007 by the Louis Riel Institute of the Manitoba Métis Federation.

A story of threads

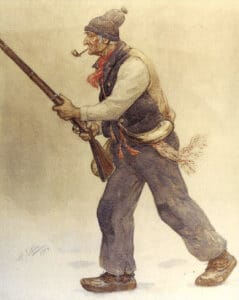

Le Patriote (Le vieux de 37) by Henri Julien. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

A few fur traders’ journals and writings of that time mentioned these “arrowed” sashes called ceinture fléchée.

- When Charles Chaboillez died, an inventory of his goods included deux cintures à flesches (2 arrowed sashes).

- E.V. Germann sketched a Canadian peasant — wearing a sash with a chevron.

- In 1798, when a drowned voyageur was found and returned for burial, Louis Généreux Labadie’s journal mentioned the canoeman was wearing “une jolie cinture à flesche” (a pretty arrowed sash).

- George Washington had a sash. After the 1755 Battle of Monongahela (in the French and Indian War), Gen. Edward Braddock presented his red commander’s sash to Washington, the only uninjured aide on his staff and the man who’d helped save the army from further catastrophe. In this YouTube video, Carol James demonstrates a sprang technique she used to duplicate Washington’s sash. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WoFMeGNshcM

By the 1820s, sashes were mass-produced in Britain by loom weavers.

Sources:

- Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America: Assomption Sash

- “Travels through Canada and the United States of North America in the Years 1806, 1807 & 1808” by John Lambert (London, 1814)

- Wikipedia: Ceinture fléschée (arrowed sash)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ceinture_fl%C3%A9ch%C3%A9e

Final Thoughts

- Book 3, “Uncharted Waters” is launched, in paper and ebook.

- Start from the beginning with Books 1 and 2 — buy “Waters Like the Sky” or “Treacherous Waters” through PayPal. Or the ebook.

- Subscribe to this blog and read posts as they are published!

- For what I’m researching or quirky discovers, visit me on Facebook or Instagram (@nlnlnraj): I love your comments.

- Book me as a speaker.

- Ask your library, local school, gift shop to buy copies.

- Be a voyageur for an hour — come to one of my presentations.

- Consider writing your own chapter — fan fiction — about what else could happen.

What I’m currently reading:

“Fur Trade Nation: An Ojibwe’s Graphic History” written and illustrated by Carl Gawboy (Animikii Mazina’iganan: Thunderbird Press, Cloquet, Minnesota, 2025)

“Our Story of Eagle Woman: Sacagawea, They Got it Wrong” by the Sacagawea Project Board of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Ariakra Nation The paragon Agency, Orange, California, 2021)

“The Red Sash” by Jean E. Pendziwol, Pictures by Nicolas Debon. (Groundwood Book, House of Anansi Press, Toronto, Canada, 2005)

Pictured above: Black Arrow sash, created in sheep wool by an artist in Saint-Boniface, Manitoba