In honor of National Canoe Day — June 26 in Canada — I created this emoji: ͼ!¡¡¡¡¡¡¡!ͻ

Canoes were built in a variety of sizes, depending on need.

Indigenous people used canoes for traveling, ricing, … and large canoes for war and trading. When the fur trade companies realized how efficient and superior the Native design and materials were, they copied them and made the largest size they could to haul cargo — trade goods one way and pelts on the return.

Montreal canoes

The canoe shed at Grand Portage National Monument shows three sizes: Montreal (top), an Indian canoe (middle) and North (bottom),

These huge canoes — the canot de maître or master’s canoe — were 35-40 feet long and about 6 feet wide. (A tennis court is about 36 feet wide.) Made of birchbark and cedar slats because they were light and strong, it weighed about 300 pounds when dry (rarely) and 600 pounds when wet. Imagine a bark vessel only 300 pounds but able to carry a burden of nearly 5 tons in weight (including the crew)!

A canot de maître was designed to carry about 60-65 bales or pièces of trade goods as well as provisions, canoe supplies and blankets and personal packs of the voyageurs — 8 to 14 canoemen needed. While paddlers today sit on seats, paddlers then knelt or sat on bales of cargo. The thwarts were not used for sitting.

Over a portage, 4 voyageurs were needed to portage a Montreal canoe — usually on their shoulders. Montreal canoes were used on the Great Lakes and large rivers like the St. Lawrence.

[In Book 1, Antoine’s brigade from Montreal to Grand Portage was comprised of 5 Montreal canoes, each propelled by 10 paddlers.]

North canoes

This canoe, with a bailing sponge inside its prow, is at the Snake River Fur Post in Pine City, Minnesota.

A North canoe (canot du nord) — about 24-28 feet long and 4 feet wide — carried 25-35 pièces, or pieces of cargo, or about 3,000 pounds (including the crew), about half of what a Montreal canoe carried. From 4 to 6 men were needed to paddle it. Because it was lighter, 2 men could portage it, and on short portages, might carry it basket-style.

It was much more maneuverable on the smaller rivers beyond Grand Portage. When fully loaded, both the North and the Montreal canoes rode low in the water, their gunwales only a few inches above the water.

[In Books 1 and 2, when Antoine, Emile, Pretty Mouse and André left Grand Portage, they purchased a canot du nord from Native Americans at the in Grand Portage. In Book 3, Andre negotiates for a North canoe to travel the Ottawa and Mattawa river system and to cross Lake Huron, where he misses the stability of a Montrealer.]

Other sizes

-

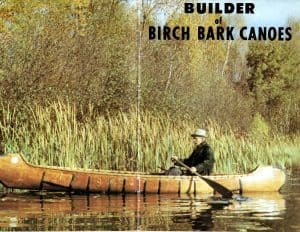

Bill Hafeman, from Bigfork, Minnesota, taught himself to build birch bark canoes.

In between the North and Montreal canoes were the batard, around 30 feet long and propelled by 16-10 men.

- A “half canoe” of about 18-24 feet long, for 3-4 paddlers, carrying 16 pièces.

- Canoes used by Native Americans were 13-16 feet long, handled by 2 paddlers — they traveled on shallower rivers and didn’t haul big loads over long distances.

- The express canoe, or canot léger, about 15 feet long, was built for speed and carried mainly important people (the bigwigs of the fur trade), reports and news — no cargo — so they could travel fast. Or in special cases, when only a larger canoe was available, its cargo was spread among the brigade and additional paddlers drawn from other canoes to add more propulsion.

- Nowadays a popular canoe length is 17 feet. It has a keel, a feature which wasn’t part of birch bark canoes.

[In Book 3, Andre is forced to trade for a light canoe once his crew gets smaller.]

These are my sources:

- “Fur Trade Nation: An Ojibwe’s Graphic History” written and illustrated by Carl Gawboy (AnimikiiMazina’iganan: Thunderbird Press, Cloquet, Minnesota, 2025)

Carl Gawboy’s graphic novel shows the canoe-building process (pages 50-55), using the direction of the grain of the bark for maximum strength.Women sewed the bark pieces together together first, giving her access to both inside and outside of the canoe. Men did the woodwork, carving and shaping the vessel. His grandparents built many canoes together, but after she passed, his grandfather never built another canoe. -

Seats have been built into this modern adaptation of Montreal canoes at Old Fort William Historical Park in Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada.

“Birchbark Canoes of the Fur Trade, Vols 1 and 2” by Timothy J. Kent (Silver Fox Enterprises, Ossineke, Michigan, 1997)

In Volume 1, Kent draws from journals of the era and paintings to fully describe everything about canoes —t among them, various hull designs, decoration, equipment and provisions, propulsion, portaging and sheltering en route. In Volume 2, he examines (in great detail) 4 canoes that survive from the 1800s and 4 scale models — together, a major reference work. - “The Survival of the Bark Canoe” by John McPhee. (Warner Books, New York, 1975)

McPhee writes of a birch bark canoe maker in New Hampshire, and then traveling 150 miles with friends in one of those amazing canoes. He includes an appendix with information from Edwin Tappan Adney, drawings and photographs - “The Voyageur” by Grace Lee Nute. (Minnesota Historical Society Press, St Paul, 1931, 1987)

Grace Lee Nute includes a whole chapter on voyageurs’ canoes, their manufacture, their materials, the daily upkeep needed in gumming the seams, the positions for paddlers (and riders), the supplies they needed — the speed of paddling and the songs sung to propel the vessel. Delightful reading!

Nikki

Final Thoughts

- Book 3, “Uncharted Waters” is launched, in paper and ebook.

- Start from the beginning with Books 1 and 2 — buy “Waters Like the Sky” or “Treacherous Waters” through PayPal. Or the ebooks.

- Subscribe to this blog and read posts as they are published!

- For what I’m researching or quirky discovers, visit me on Facebook or Instagram: I love your comments.

- Book me as a speaker.

- Ask your library, local school, gift shop to buy copies.

- Send me your own chapter about what else could happen in Andre’s life— fan fiction.

What I’m currently reading:

“Our Story of Eagle Woman: Sacagawea, They Got it Wrong” by the Sacagawea Project Board of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Ariakra Nation. (The Paragon Agency, Orange, California, 2021)

Featured image above: Bigstock

great story about one of the most important transportation devices used during the Fur Trade !!